An Attempt to Simplify Spelling: What the ITA Got Wrong – and What It Got Right

- The Reading Hut Ltd

- Jul 7

- 6 min read

The Guardian recently ran a piece titled “The radical 1960s schools experiment that created a whole new alphabet – and left thousands of children unable to spell” https://www.theguardian.com/education/2025/jul/06/1960s-schools-experiment-created-new-alphabet-thousands-children-unable-to-spell.

What amazed me most was that not a single person mentioned English orthography.

But it is about time we did, because synthetic phonics programmes are already failing 1 in 4 children in England. That, too, is a kind of failed experiment. And we still do not seem to understand how children learn to read, or why so many of them don’t.

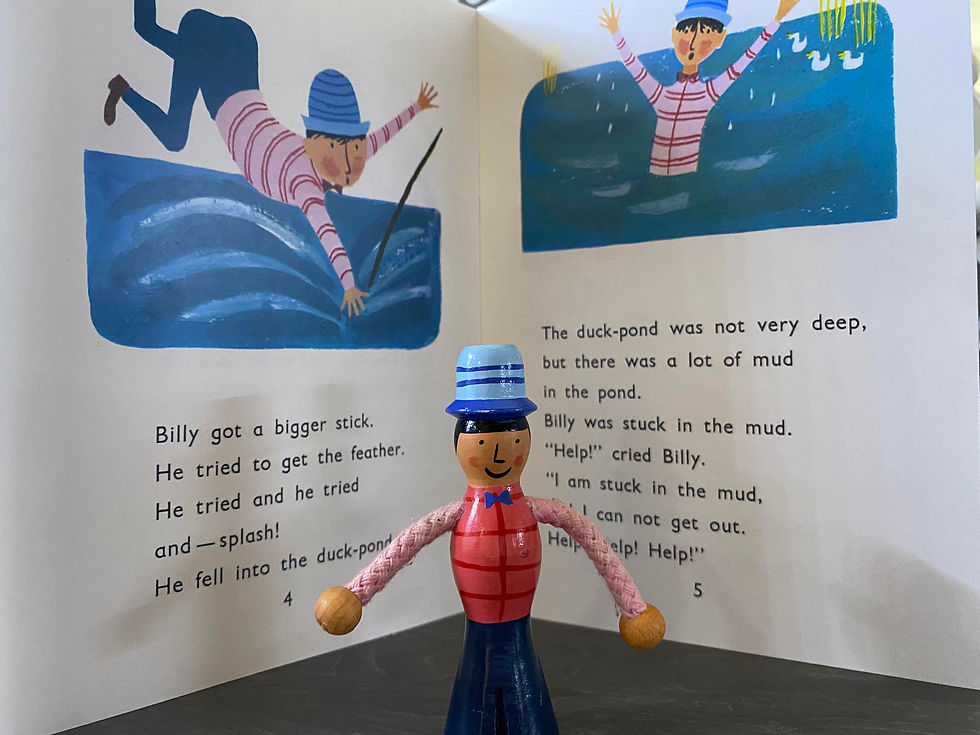

There was an image in the article with the caption: “If you are able to read these words, you might have been part of a failed English teaching initiative.”

Actually, no. If you can read, you can can figure it out. You understand how reading 'works'.

And that was the point of the experiment. It was designed to make an opaque orthography more transparent, so that people could read it.

I am not sure if the expectation was that children would then suddenly be able to read with the real alphabet, working out the graphemes and the speech sounds they represent. That would be like teaching children the IPA phonetic symbols and expecting them to go on to read and spell English without confusion.

We already have an alphabet. It has 26 letters, and these letters are used to represent at least 44 speech sounds. The letters that map to these phonemes are called grapheme–phoneme correspondences (GPCs) in England, because phonics teaching tends to focus on print-to-speech, or decoding. But mapping speech sounds to print works both ways. That is why we also need to know the phoneme–grapheme correspondences (PGCs). There are more than 350 correspondences, as seen in the Spelling Clouds. There are far too many for teachers to teach explicitly, which is why synthetic phonics programmes typically teach around 100. This is just a kick-start. Children are then expected to figure out the rest through self-teaching.

So they may see a word like orange, and even if they do not know that the /ɪ/ in in is the same sound as the third sound in orange, they will use partial decoding and the picture clues to guess the word. Children who attempt to map words using the cues are better able to self-teach. They will re-code it. The same is true for children with strong vocabulary knowledge. If they cannot decode a word entirely, they may still guess it from context. Then map back. The problem is that around one in four children cannot do this, and most teachers think 'deducing' words is something to avoid so they don't include it in their toolkit. Likely because the DfE writes things like this: "A programme should promote the use of phonics as the route to reading unknown words, before any subsequent comprehension strategies are applied. It should not encourage children to guess unknown words from clues such as pictures or context, rather than first applying phonic knowledge and skills."

This overlooks much of what we now understand about implicit learning, which is how the majority of reading development actually occurs. It's invaluable. Children are filling in the orthographic learning gaps, independently!

Because English is an opaque orthography, it is harder to learn than languages like Finnish. Sounds are represented by lots of graphemes - eg the sound /s/ has 14 - and the graphemes represent different sounds eg the /a/ maps to 9 speech sounds. The ITA was an attempt to simplify this problem, although I do not think its designers fully realised that is what they were trying to do.

The International Phonetic Alphabet shows how words are pronounced using phonetic symbols. These symbols represent speech sounds. If you want to know how to say a word, you can type it, transcribe it using IPA symbols, and blend those sounds. It is a universal speech sound spelling code. (Dehaene, Reading in the Brain. P32)

What I have done is create something new. I am the only person in the world to have transcribed words into graphemes (shown with black/ grey shading) and speech sounds using IPA Phonemies®. These are child-friendly versions of IPA symbols that help children see the structure of words in a way they can actually understand. Other than during the 10 Day Phonemic Awareness 'Speech Sound Play' plan, letters are always there however.

The ITA was a bit like writing everything in Phonemies only. It gave children access to the skills they need – especially phonemic awareness – without requiring them to learn the complexities of the alphabetic code first. But we now know that what children need is both: access to the sounds, and visibility of the graphemes. That is what we are doing with our system.

We are now creating a clickable library, and when it is ready, children will be able to read regular text or toggle to see the graphemes, or toggle again to also see the phoneme values. This way, they get the scaffolded support they need, for as long as they need it, while enjoying high-quality stories. That was part of what the ITA aimed to do too – give children the opportunity to read more widely and confidently.

By contrast, the "only read books you can decode" model used in synthetic phonics was designed by people who did not seem to realise how restrictive it would become. They ignored how crucial it is for children to enter the self-teaching phase. Ideally, children will be able to decode most of a text, even if they have not been taught every GPC yet. When they need to work out unfamiliar words using what they do know, this supports orthographic learning. That process is enjoyable, too. Children should be given texts they can figure out – not texts that simply confirm what they already know. There is a sweet spot between too easy and too hard.

As seen above, if children decode the word 'put' using knowledge from the Core Code it would rhyme with 'cut' using their GPC knowledges. This would make no sense. So they switch it! This is called Set for Variability (SfV) We WANT children to do that. The ITA wouldn't faciliate these crucial skills, as they haven't even started mapping the core code as yet.

We also need to provide mapped texts that show both the phonemes and the graphemes, so children can learn the code as they go and explore new vocabulary with confidence.

I respect those who attempted to make books more accessible for young learners. They understood the importance of phonemic awareness and the empowering experience of feeling like a reader. But it's like showing children beautiful artwork and giving them paint but never giving them a brush. I do not quite understand why The Guardian concluded that the ITA made children poor spellers. Spelling problems usually arise when children have not secured words in the orthographic lexicon – meaning they have not connected speech, spelling, and meaning. That almost always points to poor phonemic awareness. The ITA could have supported that, because to read those words, children had to blend symbols to access meaning. The images would have helped. If you cannot blend, however, you cannot read with ease. That is a phonemic awareness issue, not a spelling one.

The real issue may also have been that many children did not start learning to read with real English text until they were 7 or 8. That is far too late to begin learning to read in English within a school system. It meant they missed out on the most important two years for building phonemic awareness and understanding how sounds and letters connect. We aren't doing that very well in England at the moment. 1 in 4 become instructional casualties because phonics is not taught in a way that every child can understand.

If more people understood how children learn to read, they would understand what the ITA was trying to do. They would not adopt it, but they would see the logic in its design – and they would be more willing to build on the creative ideas behind it.

And before anyone starts pointing to Letterland or other programmes that use embedded mnemonics as the solution – that’s a different conversation entirely. One I’ll cover in another blog.

Miss Emma

Neurodivergent Reading Whisperer

The Speech Sound Pic Detective is showing the Sound Pic (grapheme) the child might not know at that Code Level. It encourages Set for Variability.

Comments