One Symbol, One Sound Unit

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system of symbols used to represent the specific sounds (phonemes) of spoken language. It was developed by linguists to provide a standardised, universal way to transcribe the pronunciation of any word in any language, regardless of spelling. We can use it to create a common language for mapping words. This means you can teach phonics throughout the day, not only during a phonics lesson. The symbols show the plausible (acceptable) sound choices for words. Plausible grapheme-to-phoneme mapping is central to Speech Sound Mapping.

A Universal Refrence Code

A major issue for teachers in England, who are required to attend to the grapho-phonemic analysis of words throughout the day, is that they are often unsure of what counts as ‘correct.’ There is no clearly defined system for mapping words, and we are creating that system. With the exception of two words (one and once), all words in English can be mapped with phonemes linked to graphemes, with every letter accounted for. The IPA provides a way to see the acceptable sound values, which may vary by accent, and this variation can be openly discussed with learners. However, the universal reference code serves as the agreed point of consistency. Learners can also explore plausible graphemes, as illustrated in the Spelling Clouds®.

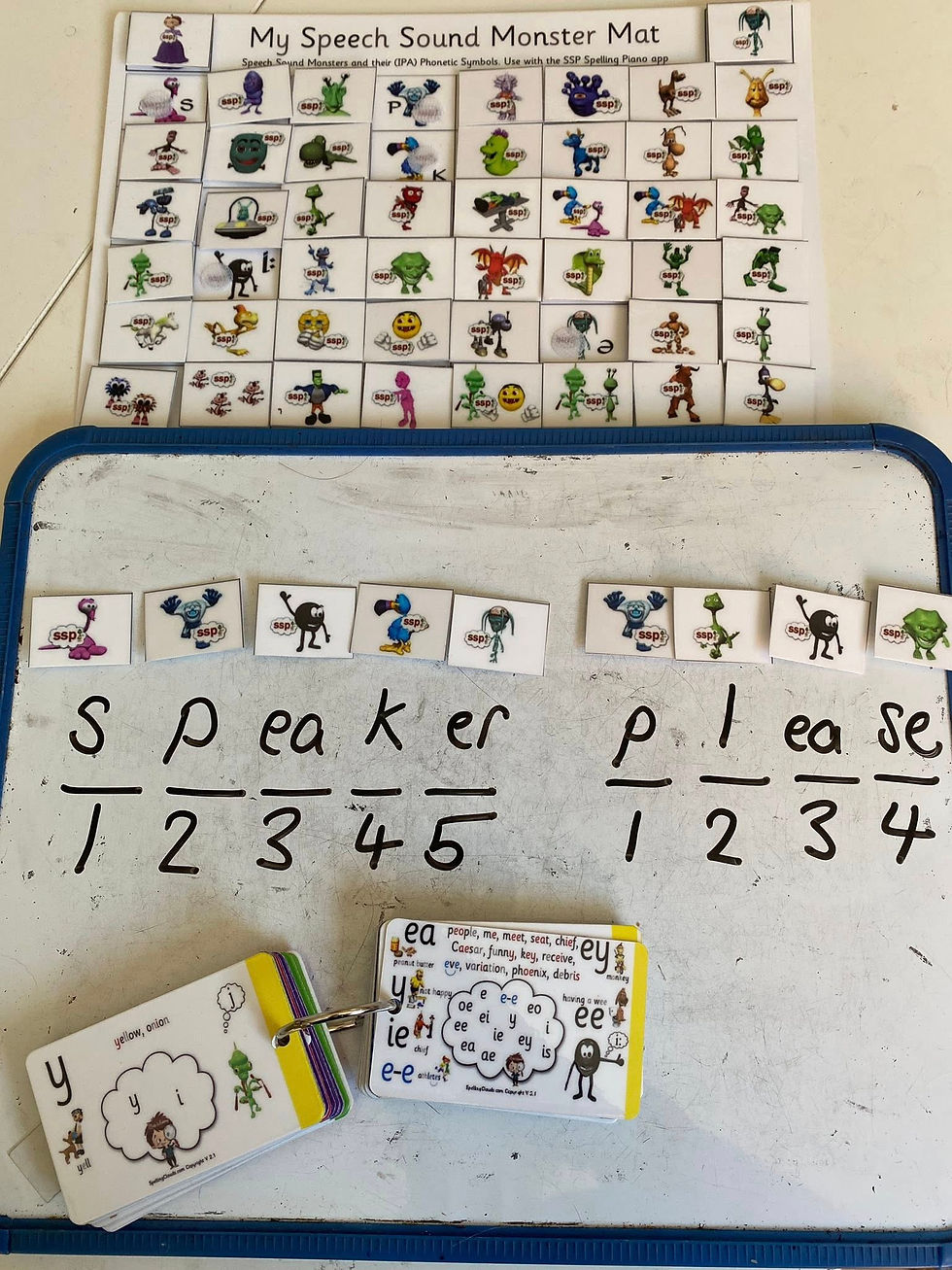

Mapped Words® present the plausible correspondences that can serve as the universal reference code, but after blending the sounds, the word may still be pronounced differently by the learner. When spelling with the child’s own speech sounds it is essential to always show the universal reference code. Adults can use the IPA with code mapped words, children reference the Phonemies.

Children using the Speech Sound Pics Approach read the story about the Speech Sound King creating this code, which is why the universal reference code is based on his accent (Received Pronunciation). They blend using his sounds and spell with them through the Mapped Words® and Mapped Books. By working with the universal reference code, learners soon begin to understand how the code operates and adapt it more easily to their own speech. This creates far fewer difficulties in understanding, and it supports all brains.

Key Points:

-

Each IPA symbol - and therefore Phonemie- represents a single phoneme, not a letter. Phonemes are the smallest units of sound that can change the meaning of a word, such as /p/ and /b/ in pat and bat.

-

Not all phonemes (Monster Sounds) are produced with a fixed mouth position. For example, /z/ or /s/ are steady sounds, with the tongue and mouth remaining in roughly the same place from start to finish. In contrast, vowel phonemes such as /uː/ and /eɪ/ (as in Tuesday /are diphthongs. These are single phonemes, but they involve movement during production. The shape of the mouth and position of the tongue change while the sound is being made.

Say moo (/m uː/). You may notice that the /uː/ sound seems to slide or glide, almost as if there is a /w/ at the end. This happens even though /uː/ is just one phoneme in English, and in this case maps to the /oo/ grapheme. -

This means a single IPA symbol, or symbol pair, can represent a phoneme that moves during production. This movement does not mean there are two phonemes; rather, it reflects the dynamic nature of some speech sounds.

-

The IPA is based on how phonemes function within a language system. It does not always reflect slight differences in articulation, unless a more detailed phonetic transcription is used. For example, the /t/ sound in top and stop is not identical in English, but both are typically transcribed as /t/ because they do not change the meaning of the word.

-

Phoneme realisation can vary across accents and speakers. For instance, the /r/ phoneme is pronounced differently in Scottish and southern British English, yet it functions in the same way within each system. The IPA symbol stays the same, even when the precise sound quality differs.

Why This Matters for Teaching Reading and Spelling

Phonemes are often taught as simple and fixed, but many involve noticeable movement during articulation. This can cause confusion for both teachers and learners. Children may struggle to match a written grapheme to a phoneme that changes as it is spoken. For example, if a teacher describes /əʊ/ as "just one sound," but the child hears a shifting sound, the mismatch can interfere with their ability to map speech to print.

To further complicate matters, some graphemes represent more than one phoneme depending on the word. For example, the grapheme <x> maps to two phonemes in words like ox /ɒks/, luxury /ˈlʌk.ʃəri/, and exit /ˈɛɡ.zɪt/ or /ˈɛk.sɪt/, but to only one phoneme in xylophone /ˈzaɪ.lə.fəʊn/. The /k/ and /s/ sounds together can also map to the grapheme <xe> as in axe /æks/.

Other inconsistencies arise in vowel–consonant combinations. In blue /bluː/, the digraph <ue> maps to a single phoneme /uː/. However, in cue /kjuː/, <ue> forms part of a sequence that maps to two phonemes /j/ and /uː/. In this case, the same grapheme string <ue> plays a different phonological role depending on the word.

Understanding the IPA while mapping words can help teachers become more aware of the complexity of speech sounds and the nature of the phonemes they are teaching. This awareness is especially important when supporting children with speech differences, non-standard pronunciations, or learning differences and therefore additional learning needs.

One practical step is to begin mapping words with children during everyday activities. This is 'Discovery Phonics' or 'Spontaneous Spelling'. When a child asks how to spell or read a word, the teacher cannot support that child if not themselves confident in identifying the phoneme–grapheme correspondences in that word, using a shared and systematic reference. HOW they do this may vary, whether they show the child, or use a specific routine or strategy, but they must know the target correspondences. This includes being aware of how accent and connected speech can affect mapping. For example, consider the word can. In isolation, when teaching phonics, it would be modelled by the teacher and pronounced /kæn/. But in connected speech, such as I can run quickly to the park, it is more likely to be realised as /kən/, where the /æ/ sound becomes /ə/. This type of variation affects how children perceive and produce the sounds they are trying to map to print. If a child says - in their mind- the sentence they want to write, and say it as aɪ kæn rʌn kwɪkli: tuː ðə pɑːk they are hearing kən and have been told to write the word using the sounds they hear. This is is also why error analysis matters so much. If your student wrote I cun run... would you recognise why? Understanding errors helps you understand the congitive processes involved, and better support your learners. Simply telling them 'the sounds are k æ n wil confuse the child who is saying the word within a sentence!

By making the phoneme–grapheme relationships visible and discussing variation explicitly, teachers can better support all learners, especially those who struggle with phonemic awareness and orthographic learning.

Use the Phonemies Screen in the MyWordz® tech or the Monster Spelling Piano app